Helicopter crash survivors speak about their ordeal

Kirsty Macnicol

26 April 2019, 5:36 AM

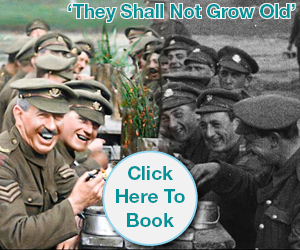

A story of survival: (from left) winch operator Lester Stevens, paramedic John Lambeth and pilot Andrew Hefford with the immersion suits all three were wearing when their helicopter went down in the Southern Ocean this week.

A story of survival: (from left) winch operator Lester Stevens, paramedic John Lambeth and pilot Andrew Hefford with the immersion suits all three were wearing when their helicopter went down in the Southern Ocean this week.The three Te Anau men who survived a helicopter crash near the sub-Antarctic Islands on Monday night said they never doubted they would be rescued, but knew their loved ones at home would be fearing the worst.

The three crewmen – pilot Andrew Hefford, paramedic John Lambeth and winch operator Lester Stevens – came together today to speak to media about their ordeal and thank the community for their support and well wishes.

They were en route to Enderby Island on Monday night to retrieve a sick seaman from a vessel in the Southern Ocean when they disappeared from communications shortly after 7.30pm.

With the incident under investigation by the Transport Accident Investigation Commission, none of the trio elaborated on what might have contributed to their predicament other than to saying flying conditions had been “good” and the impact when they hit the water was “pretty violent”.

Mr Lambeth said his training kicked in almost immediately – even to the point that he closed his eyes for a moment to collect his thoughts and orientate himself before disconnecting his headset, releasing his seatbelt and getting the door open.

“It was certainly dark and the water flooded the cabin very quickly,” Mr Lambeth said.

“I can freely admit there was a few seconds of sheer panic there. Releasing myself, I floated up and hit an object above me and, to my own mind ‘I’m going to drown, I’m going to drown’, then threw myself out of that and out of the ‘copter.”

As soon as he took a breath he knew he wasn’t going to drown and he credited his training with giving him the wherewithal to block out all distractions and focus on what needed to be done.

“It’s that training that has pulled us through this, without a doubt.”

“I went round to the back of the helicopter, to the rear of it and Lester, beside me here, was unresponsive lying in the back of it filling with water. Heff started yelling from the other side so immediately there was some relief that the guys were with us.”

“The volume of water that was around the rear of that aircraft was just phenomenal. I’m only surmising it was well over half full, well over, and we needed to get clear of that aircraft.”

Mr Lambeth pulled Mr Stevens from the helicopter and was then joined by Mr Hefford who, after initially swallowing some salt water and thinking “this is it” was also able to rely on his training to get clear. The door on his side of the helicopter had gone but his seatbelt was still secure.

“We just started to get a game plan, between me and Heff, what we needed to do and by that time the helicopter was gone,” Mr Lambeth said.

They managed to grab a couple of night vision google cases to use as flotation devices. Mr Lambeth then grabbed what he initially thought was the life raft and they swam the 100m or so to shore.

It was during the swim that Mr Stevens regained consciousness, which he described as like waking up from a weird dream.

“I woke up on my back on the water and someone was saying something about swimming,” Mr Stevens said. “I wondered what the hell they were talking about really. I had no idea where I was or why I was swimming at that stage. Eventually I came to my senses as to what exactly had happened and just lay on my back and kicked while the others swam beside me.”

Winch operator Lester Stevens (left) who was knocked unconscious and pulled from the helicopter by paramedic John Lambeth (right) before it sank .

When they reached land, they clambered over slippery kelp and onto a rock to pause and take stock of their injuries. Mr Stevens had a bleeding nose (later diagnosed as broken) and limited movement in his right should (later confirmed as an AC tear). Mr Hefford had a sore back (and would later be diagnosed with a fracture to his T12 vertebrae). Mr Lambeth had sore ribs (later confirmed as one broken rib and bruising).

“There was nothing that was life threatening and going to cause us significant issues,” he said.

Mr Stevens said he sea was relatively calm and they weren’t thrown against rocks as they might otherwise have been.

“We were extremely lucky as far as the weather and wave action were concerned and I never doubted that we were going to get somewhere safe,” he said.

However, they were still some distance from “safe”. Ahead of them were huge cliff faces and a high tide mark that was well above the rock they had made it to.

“There was no way we could stay there,” Mr Lambeth said. “Andrew was quite clear that we should go right, towards Enderby [Island], towards the hut at that end potentially, so right we went.”

It was at that point they realised the bag Mr Lambeth had dragged from the helicopter was not the life raft as he had thought but Mr Stevens’ gear bag which contained nothing of use to them, so they abandoned it. However, Mr Lambeth remembered he had a headtorch in his trouser pocket under his immersion suit and was able to retrieve it. Fortunately, it worked.

The next 30m to 40m were “pure hell”, repeatedly climbing over kelp beds, clinging onto rocks, and back into the sea again as they worked their way around the cliff face for about an hour.

“We got to a point where there was a stream coming down and another sheer cliff face… it was quite apparent we weren’t going to be able to go any further so it was ‘up we go’ so we managed to follow this creek bed up and into the bush line.”

Well briefed on the weather forecast before they left, they knew there was a “reasonably serious weather front” expected around 2am. They found a hollowed-out log and set about making themselves as comfortable and dry as possible for the night. The immersion suits all three were wearing had aided with buoyancy in the water and kept them “wet and warm” while in the water and while moving on land.

“[The immersion suits] were certainly the difference between life and death in terms of where we were.”

However, the wind chill at night meant they were wet and cold and had to huddle together to make their most of their shared body heat.

Mr Lambeth said their minds drifted to those at home during the long night hours.

“We knew we were safe, we knew we were going to get out of this and we certainly talked about the hell on earth that was being created back here in terms of their anguish and not knowing what was going on,” Mr Lambeth said.

“The magnitude of what was inevitably going through their minds – we all know the results in helicopter crashes is generally not favourable. We held close to that, you know, that we’ve got through this and will come out the other end, but we really could feel for the troops back here just what they were going through.”

Mr Stevens said when someone requiring assistance was able to set off a personal locator beacon at least those looking for them could take some comfort in knowing someone was alive. In this case none of them had been able to reach the beacons in their dry bags. Mr Stevens said he always carried a locator beacon in his overalls but was not wearing them on this occasion because he was a late call-up to the mission and had been picked up on his way home from holiday.

During the night they heard the Royal New Zealand Air Force P-3 Orion flying overhead so they knew the search process had begun.

“We always knew they were on their way, we just had to wait it out,” Mr Hefford said.

That didn’t mean it was a comfortable wait, Mr Lambeth said.

“We were clock-watching. We know the timeframes to get down there and the weather fronts that were coming through that would possibly hold them up.”

Hunger didn’t cause them concern, but they were beginning to get thirsty as water in the creek nearby didn’t look safe to drink.

The emotions that arose when they finally heard the familiar sound of the Squirrel helicopter containing Southern Lakes Helicopters owner Sir Richard Hayes and pilot ‘Snow’ Mullaly were indescribable.

“How appropriate that the people we work with so, so closely with on all sorts of missions, are the ones to come and find us. It couldn’t have ended any better,” Mr Lambeth said. “You just can’t explain the emotion that goes around that.”

“These are our work colleagues, they know how it is in the big world and here we are all alive and so we just soaked that emotion up really. There were some big hugs that went on around that beach, which was really, really – well I won’t forget that.”

Back at Enderby Island Mr Lambeth said they were also able to speak to their families.

“There was a lifetime pause on the phone on my behalf to stop the emotions and the jelly legs just overtaking really… Linda, my dear wife, just said ‘it’s so nice to hear your voice’ and that’s it in a nutshell.”

While many have described the trio’s safe return as a miraculous outcome, none of those involved said they believed in miracles but said luck was certainly on their side. They credited the proximity of the crash site to land, the quality of their training which led to their ability to make correct decisions at the time and the skill and determination of those tasked with finding them as crucial elements in their survival.

Mr Stevens said he wanted to publicly thank Mr Lambeth and Mr Hefford for looking after him until he was able to look after himself.

“It sounds like I was history without their help.”

But he also gave thanks to the countless well-wishers in the community.

“I know the community’s been ecstatic that we were all found safe and well and we’d just like to thank them all for their help and support of the families.”

Mr Lambeth said they were humbled by the support offered to their families during the search and for the outpouring of elation at their return.

“Someone’s taken the time to welcome us home with a sign on the gate at Southern Lakes. That cuts pretty close because it’s just who the community is here. As a group we hold together. Outstanding response and support.”

Mr Lambeth also paid tribute to the strength of the trio’s families throughout the ordeal.

“In my mind they’re the ones who have done the real emotional hard work. We did the physical stuff at our end to get out of that scenario, they’ve done the emotional work.”

And all three said they’d be keen to return to their duties as soon they had medical clearance to do so.